2a. From Deep Generative Models (DGMs) to Constrained Deep Generative Models (C-DGMs)

How to Make Synthetic Tabular Data Realistic by Design

In the last post, we explored why adversarial examples for tabular data must be realistic. A negative age, a bank account with inconsistent balances, or a medical record with incompatible diagnoses may succeed in bypassing a model, but they are meaningless in practice. They belong to a space of points that cannot exist, and as such they represent useless threats. Our goal is not to discover these impossible cases, but to identify the ones that truly matter. The realistic adversarial examples that expose vulnerabilities models will face in the real world.

Deep Generative Models (DGMs) such as GANs, VAEs, and diffusion models seem like a natural candidate for this task. They’re powerful and efficient, capable of learning complex data distributions and generating synthetic data that closely resembles real samples. This makes them a practical option for producing adversarial examples at scale.

But here lies the problem:

Statistically plausible does not necessarily mean “feasible”.

When we tested popular tabular DGMs on six real-world datasets, we ran into some challenges. A large portion of the generated samples (sometimes more than half) failed to meet even the most basic feasibility constraints. In some datasets, nearly every generated record was invalid, with violation rates reaching as high as 95 to 100%. In theory, you could try filtering out invalid outputs by repeatedly generating new ones until you get a valid sample. This technique is called rejection sampling, but it stops being practical if most samples are rejected.

The problem is straightforward: a model that merely captures statistical plausibility is not enough. To be useful for adversarial testing, or even for generating synthetic data more broadly, we need generative models that are realistic by design. That means models that respect the rules of the domain, not after the fact through rejection sampling, but as an integral part of the generation process.

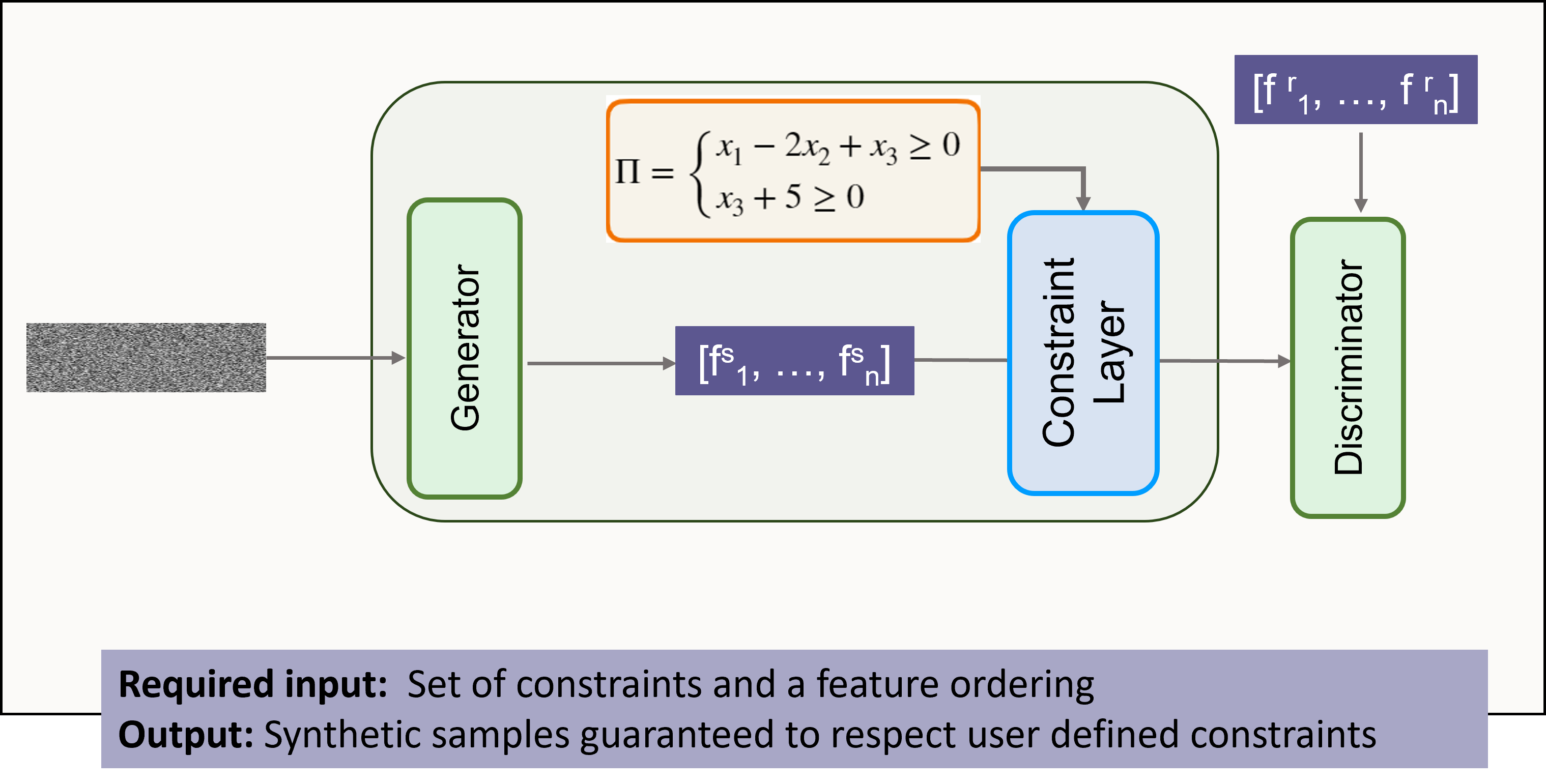

The Constraint Layer: Adding a Rulebook to Deep Generative Models

Before DGMs can be used for adversarial testing, they must first produce data that makes sense. That is where the Constraint Layer (CL) comes in. Inspired by neuro-symbolic AI, the CL acts as a rulebook embedded inside the generator. Its job is simple but crucial: check each generated record against a set of user-defined constraints, and if any rules are violated, nudge the values just enough to bring the record back into the feasible region. The correction is always minimal, so the repaired record stays as close as possible to what the generator originally produced.

Constraints can capture simple rules, like ensuring age ≥ 0, or more complex structural relationships, such as total_income = salary + bonus + other. By enforcing these user-defined linear constraints directly during generation, the CL ensures that every output respects the domain’s ground truths rather than producing “plausible but impossible” data.

An important detail is the order in which features are repaired, which is also specified by the user. Since features often depend on one another, the CL processes them sequentially according to this ordering. The sequence can follow the feature indices, be randomized, or be guided by causal or logical relationships in the data. Choosing the order carefully helps the CL make minimal adjustments while preserving the integrity of the generator’s learned distribution.

Example: How Feature Ordering Matters

Consider a dataset with three features: salary, bonus, and total_income, with the linear constraint total_income = salary + bonus.

Suppose the generator produces a sample where: salary = 50 ^ bonus = 20 ^ total_income = 60. The constraint is violated because 50 + 20 ≠ 60.

The constraint layer repairs features sequentially based on the user-specified ordering:

-

Order 1: salary → bonus → total_income

The CL first checkssalary (50)andbonus (20), then adjuststotal_incometo70. -

Order 2: total_income → salary → bonus

The CL first adjuststotal_incometo70, then checkssalaryandbonus(both fine).

In this simple example, both orders produce valid outputs, but in complex datasets with interdependent features, the ordering affects which features are minimally changed and how closely the repaired sample matches the original generator output. Ordering based on causal or logical relationships helps preserve the generator’s intended distribution.

Because the CL is differentiable, it can be integrated into the training phase, so the generator gradually learns to produce valid samples directly. It can also act as a guardrail at inference time, repairing invalid outputs even for pre-trained or black-box models.

With this addition, ordinary DGMs become Constrained DGMs (C-DGMs), generators that not only capture statistical patterns but also obey the rules of the real world. This foundation sets the stage for the next step: extending C-DGMs into adversarial generators capable of producing realistic, constraint-respecting attacks.

But before we go there, let’s look at what we observed.

- Constraint violations. With the constraint layer in place, feasibility violations dropped to zero. Unlike standard DGMs, which often produced invalid or inconsistent tabular records, C-DGMs generate samples that consistently respect domain rules. This makes them suitable for adversarial testing.

However, the benefits of constrained generation go beyond adversarial testing. By ensuring that generated data is valid and realistic, C-DGMs can support a variety of practical applications: they enable the creation of privacy-preserving synthetic datasets, facilitate fairness auditing through plausible counterfactuals, provide useful data augmentation for small or imbalanced datasets, and generate reliable test cases for validating machine learning systems in safety-critical domains such as healthcare and finance.

-

Utility. As a side experiment, to prove the benefits of C-DGMs beyond adversarial testing and to evaluate the overall quality of the synthetic data, we trained downstream classifiers on the generated samples. Models trained on constrained data outperformed those trained on unconstrained samples by up to 6.5% on utility metrics, demonstrating that the data is not only valid but also informative.

-

Runtime. Remarkably, these improvements came at minimal computational cost. Generating 1,000 samples with the constraint layer added only a few hundredths of a second, indicating that constrained generation can scale efficiently to larger datasets.

These results, along with additional findings and more detailed explanations of the construction of C-DGMs, are described further in How Realistic is Your Synthetic Data? Constraining Deep Generative Models for Tabular Data.

Now with the foundation of C-DGMs in place, the next step is to explore adversarial generation. If C-DGMs can reliably generate valid samples, can they also generate adversarial ones that are both realistic and effective? That’s the challenge we’ll tackle in the next post.

Note: This blog series is based on research about the realism of current adversarial attacks from my time at the SerVal group, SnT (University of Luxembourg). It’s an easy-to-digest format for anyone interested in the topic, especially those who may not have time (or willingness) to read our full papers.

The work and results presented here are a team effort, including Asst. Prof. Dr. Maxime Cordy, Dr. Thibault Simonetto, Dr. Salah Ghamizi, (to be Dr.) Mohamed Djilani, (to be Dr.) Mihaela C. Stoian and Asst. Prof. Dr. Eleonora Giunchiglia.

If you want to dig deeper into the results or specific subtopics, check out the papers linked in each blog post.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: