1. The Limits of Adversarial Text Attacks

When AI Gets Fooled but Humans Don’t.

In the first post of this series, we introduced adversarial attacks as a security threat to AI/ML systems. We also discussed why realism matters when evaluating and defending against them. Yet defining and reproducing “realistic” conditions is already difficult for many applications. In this post, we’re zooming in on natural language processing (NLP) to see why these challenges are even harder when the medium is language.

For image-based adversarial attacks that we have seen so far, realism is often defined by imperceptibility. Mathematically, this is captured by minimizing the distance between the original and adversarial image using Lp norms. For example, the L1 norm sums up all the small differences in pixel values compared to the original image. Smaller distances mean the images look almost identical to the human eye. The goal is to make changes so subtle that people don’t notice them, while still fooling the model.

With text, however, things are much trickier. A tiny change, such as swapping “movie” for “mov1e” might deceive a classifier, but it is immediately obvious to any human reader. This disconnect matters because, in many NLP applications, humans remain part of the decision-making loop. A phishing email with awkward phrasing probably won’t get clicked, even if a sophisticated AI/ML filter fails to catch it. A fake news headline that “feels off” will raise suspicion, even if it bypasses automated detection. Offensive language that appears altered won’t convince moderators, even if the model is fooled. In these scenarios, an attack is only truly dangerous if it can deceive both algorithms and humans. This means that creating a realistic and effective adversarial example requires thinking about how humans interpret text, not just how models process it.

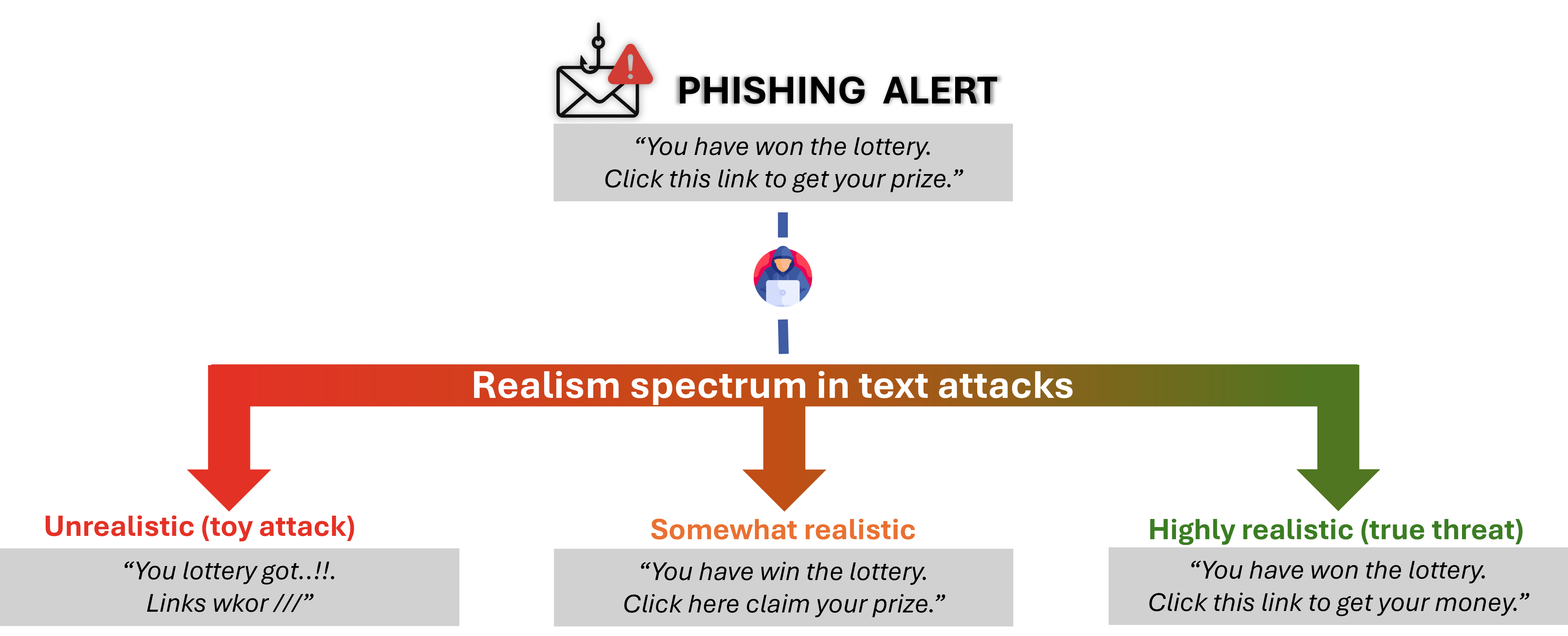

To understand realism for text attacks, it helps to see it as a spectrum. At one end are unrealistic attacks that are easy for humans to detect, but may still confuse automated models. In the middle are somewhat realistic attacks that sound plausible but still raise suspicion. At the far end are highly realistic attacks designed to deceive both humans and AI/ML systems.

Attack realism in text-based use cases, can be viewed as a spectrum.

To illustrate, consider the phishing examples in the figure above:

-

Unrealistic (toy attack):

“You lottery got…!! Links wkor ///”

These attacks are nonsensical and grammatically broken. Humans would easily dismiss them, but some detection models might still misclassify them. -

Somewhat realistic (model fooled, humans suspicious):

“You have win the lottery. Click here claim your prize.”

The message is understandable but clunky and unpolished. Many automated filters might fail to flag it, yet most users would still hesitate to trust it. -

Highly realistic (true threat):

“You have won the lottery. Click this link to get your money.”

This represents a serious security risk. The message is fluent, grammatically correct, semantically coherent, and persuasive enough to bypass both detection systems and human judgment.

Real attackers aim for highly realistic adversarial text to maximize success while avoiding detection. Consequently, most NLP robustness tests try to preserve meaning, grammar, and natural style so the attacks resemble real-world scenarios. However, these methods often rely on mathematical proxies that miss the subtle cues humans use to judge whether a message is suspicious. Our survey of the literature shows that human perception is rarely included in evaluations: 3 of 16 studies involved no human participants, and those that did often rely on just a handful of people (1–3) assessing narrow aspects like meaning preservation or label consistency. Such limited checks overlook the broader ways humans detect suspicious text.

To address this, we conducted one of the first large-scale studies on human perception of adversarial text, surveying 378 participants across nine state-of-the-art attack methods to see how people actually respond. We focused on two key aspects of how humans perceived the adversarial texts:

-

Validity: Does the text preserve its original intent after being manipulated?

For example, if a hateful message like “I hate all XXX” is changed to “I love XXX,” the model might be fooled, but the attacker’s goal fails because the meaning that reaches the end user has been completely reversed. -

Naturalness: Does the text appear manipulated or computer-generated to a human reader?

Even if an adversarial text is valid, one that feels awkward, unnatural, or obviously altered may fail to convince people.

The results showed that what fools models often does not fool humans. We explore these findings and their implications in our ACL paper, “How Do Humans Perceive Adversarial Text? A Reality Check on the Validity and Naturalness of Word-Based Adversarial Attacks”.

-

Validity: Humans correctly understood the original intent of about 72% of adversarial texts, compared to nearly 89% for the original texts. This shows that many attacks produce a significant portion of invalid adversarial examples.

-

Naturalness: Adversarial texts also stood out as unnatural. Over 60% of participants flagged them as likely computer-generated, compared to just 21% for the original texts. When asked to pinpoint the changes, participants identified the altered words in roughly 50% of the cases. This shows that while adversarial examples may fool models, they often fail the human “readability and believability” test.

These results show that even the most advanced attacks today often wouldn’t succeed in real-world settings where humans are part of the system. This is relevant for cases like content moderation, or misinformation control, where human judgment remains a critical part of the system, as we discussed in the introduction.

Out of curiosity, we also explored why certain texts trigger human suspicion. From there, we could observe the following trends:

- Clear meaning matters: Texts that preserved their original intent and were easy to understand were generally seen as more natural, while messages with unclear or distorted meaning were much more likely to be flagged as “computer-generated.”

- Grammar errors, not as much: Minor grammar mistakes didn’t necessarily make a text feel unnatural if the meaning was clear. But once a message became awkward or nonsensical, it immediately stood out to readers.

These were the main results, and for full details you can check out our paper. Few were the main lessons, from this large-scale human study. It became clear that human psychology plays a major role in whether an attack succeeds. Focusing only on model performance misses an important point: human judgment gives a more realistic perspective for many applications. Future research on adversarial testing in NLP should focus on crafting examples that are semantically valid, natural, and persuasive, while keeping humans in the loop to accurately assess real-world threat potential.

A small disclaimer: Our study predates the recent surge in Large Language Models (LLMs). These systems generate fluent, convincing text that may appear far less suspicious, posing new challenges for adversarial NLP research.

Note: This blog series is based on research about the realism of current adversarial attacks from my time at the SerVal group, SnT (University of Luxembourg). It’s an easy-to-digest format for anyone interested in the topic, especially those who may not have time (or willingness) to read our full papers.

The work and results presented here are a team effort, including Asst. Prof. Dr. Maxime Cordy, Dr. Thibault Simonetto, Dr. Salah Ghamizi, (to be Dr.) Mohamed Djilani, (to be Dr.) Mihaela C. Stoian and Asst. Prof. Dr. Eleonora Giunchiglia.

If you want to dig deeper into the results or specific subtopics, check out the papers linked in each blog post.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: