3. From Testing to Defenses: When Realistic Attacks Help

Finding the attacks that teach models to defend themselves.

So far in this series, we’ve seen how adversarial testing often relies on unrealistic attacks, giving AI developers a false sense of security. What testing really provides is a map of weaknesses. It shows where the shield has cracks. The real challenge comes next: hardening those weak points, so the shield can withstand real-world attacks. As researchers and practitioners, we must remember that testing is only a tool. The ultimate goal is defense.

Hardening means repeatedly exposing your model to attacks and forcing it to adapt. You generate adversarial examples, retrain the model using the true or intended labels for those examples, test again, and repeat the cycle. Over time, the model learns to resist the tricks attackers are likely to use. In practice, this process goes by different names depending on technical variations, such as adversarial training, retraining, or fine-tuning. Regardless of the name, the goal is always the same: to expose the model to hostile conditions so it is prepared for real-world attacks.

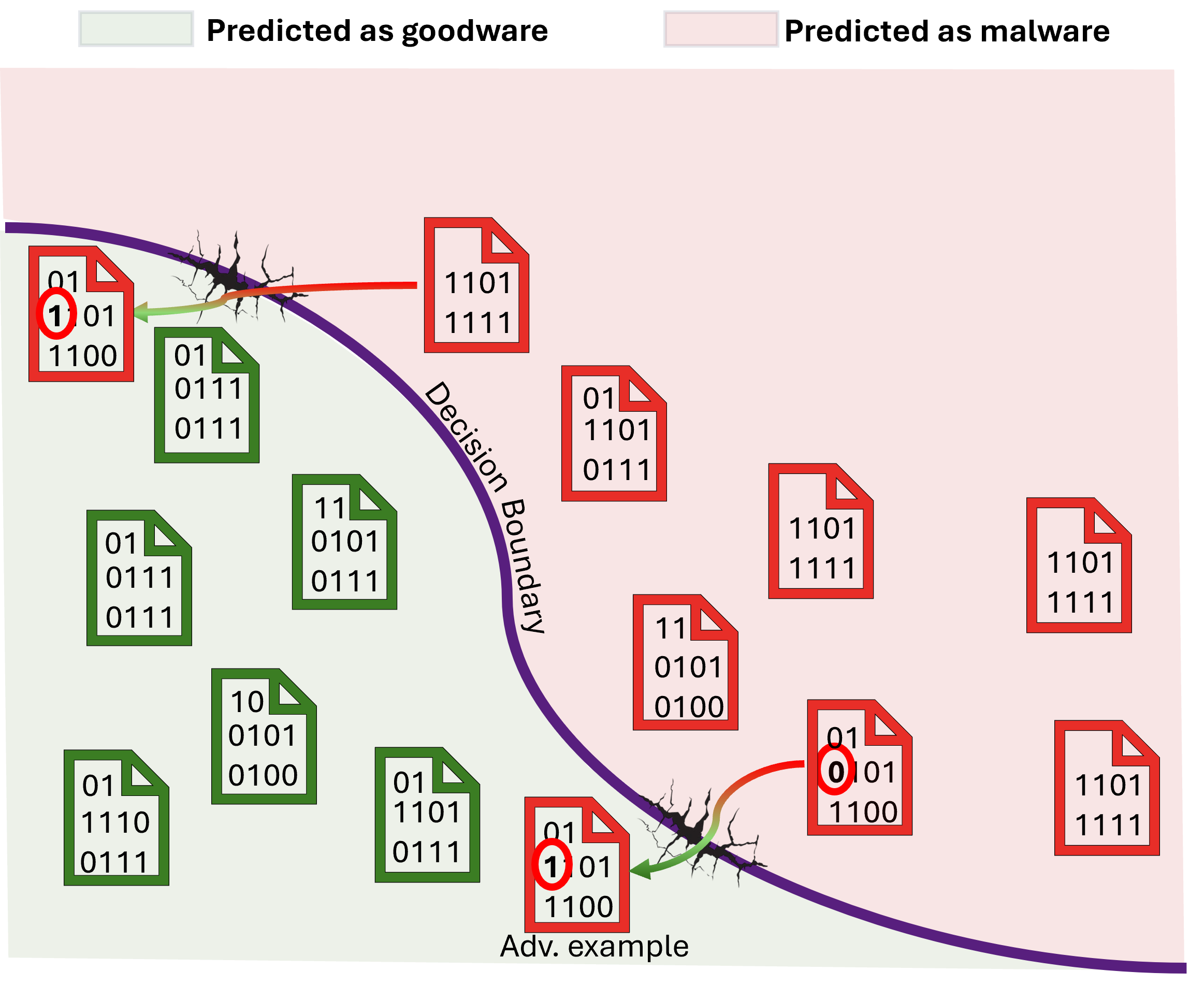

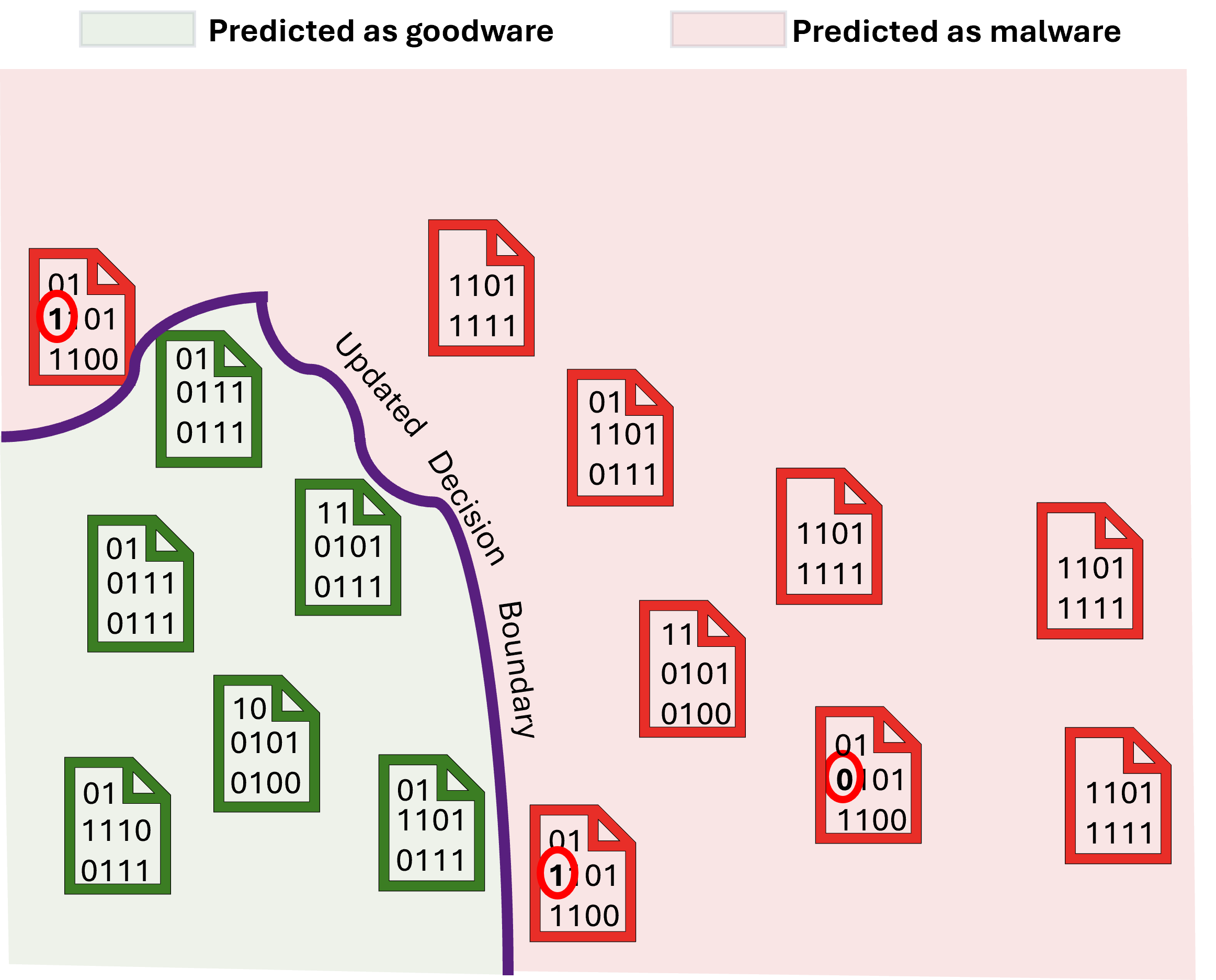

In the figure below, left side shows a malware detector identifying malware files. We then create adversarial examples, shown as the two files with arrows, that exploit weaknesses in the model’s decision boundary. In right side, the model has been retrained using these adversarial samples, which updates the decision boundary. The model can now correctly detect the files that previously slipped through. While the figure uses only two examples for illustration, in practice retraining would involve thousands or even hundreds of thousands of samples to make the model significantly more robust.

Decision bounadary before adversarial hardening

Updated decision boundary after retraining on adversarial examples

Figure: A malware detector predicting Windows binary files as being malicious or not

But here’s the key question:

Does the realism of adversarial examples used in hardening matter?

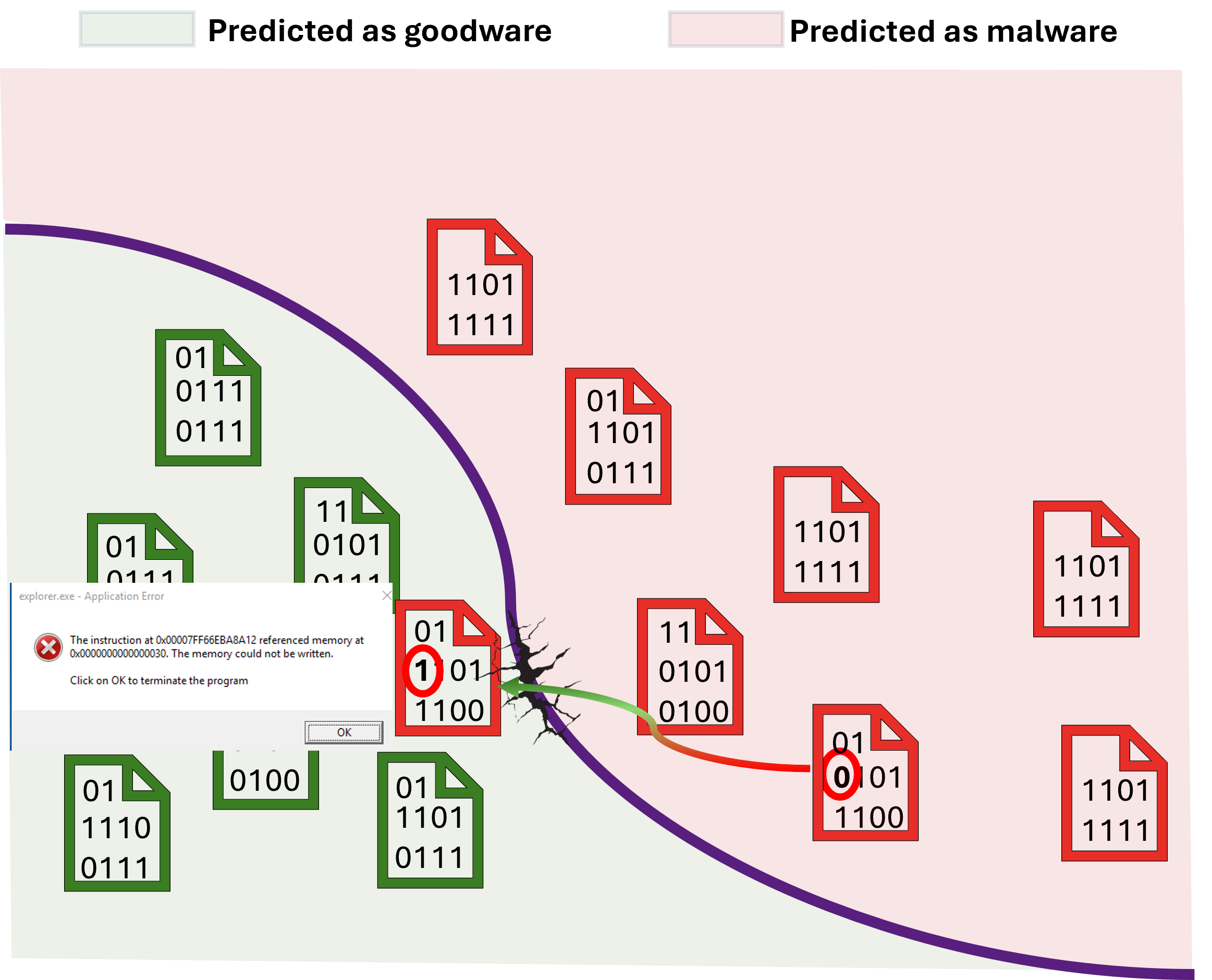

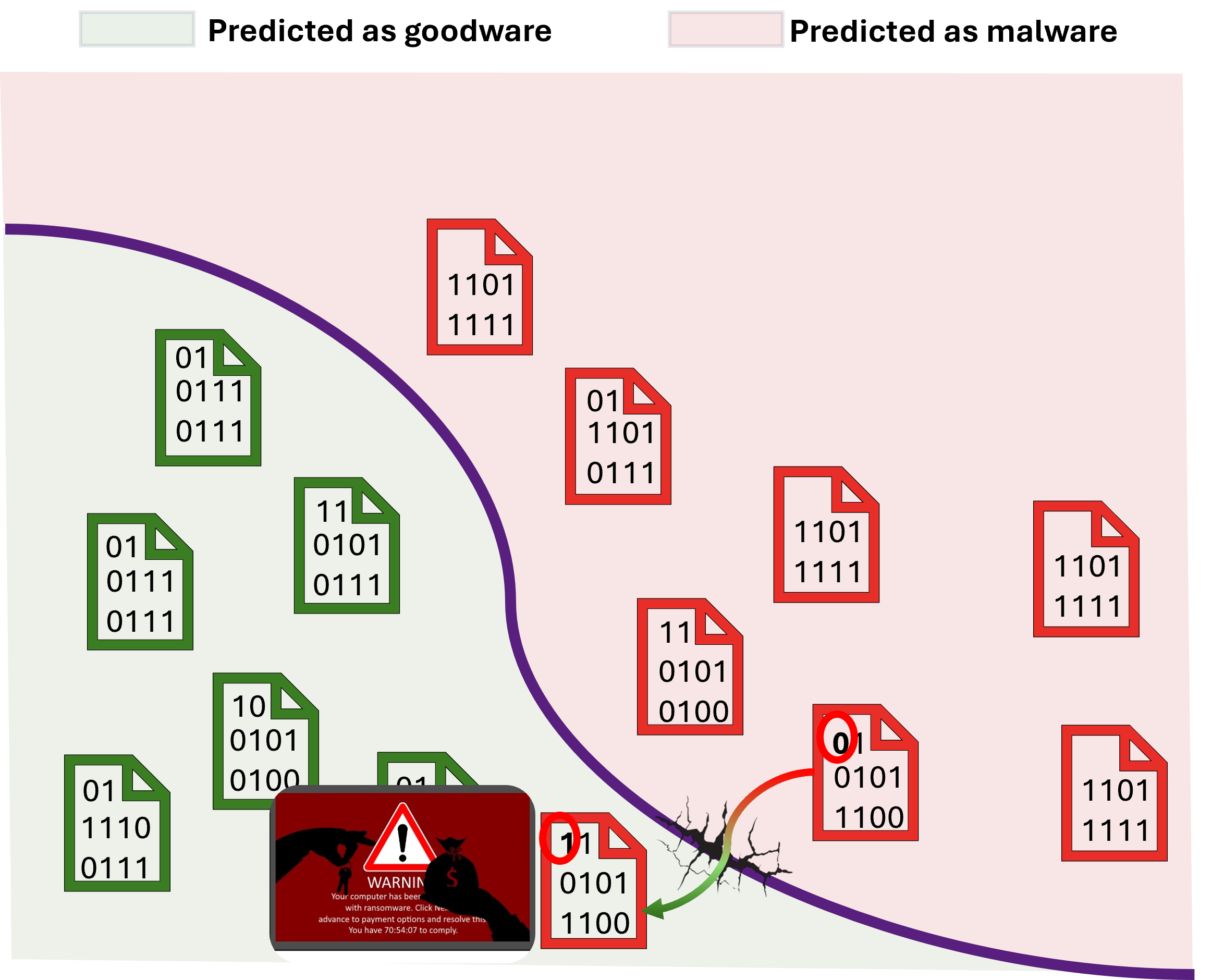

Consider the malware detector above. An unrealistic attack might modify a malicious file in ways that break it. Even if the detector lets it run, the attack fails because the file cannot execute. A realistic attack, by contrast, carefully modifies the malware to evade detection while still achieving its malicious goal, such as locking the computer, making it much harder to stop. If the model is trained only on unrealistic examples, it may still fail against realistic ones. This uncertainty is exactly what our study set out to investigate in On the Empirical Effectiveness of Unrealistic Adversarial Hardening Against Realistic Adversarial Attacks.

Generating unrealistic attacks is fast and inexpensive because they can be created without worrying about whether the file will execute. Crafting realistic attacks, by contrast, is far more costly in both computation and engineering effort. Modifying malware to evade detection requires carefully changing executable files without breaking them and testing them in a specialized sandbox to ensure they still carry out their malicious purpose (e.g., asking for ransom). This process can take tens of thousands of times longer than simply altering a few bytes at random, which can take days or even weeks. If unrealistic examples can expose the same weak points in the model’s decision boundary as realistic attacks, they could serve as effective stand-ins, potentially saving substantial time and resources in the hardening process.

Unrealistic example (malicious file that does not execute)

Realistic example (infects computer and asks for ransom)

Figure: Adversarial examples used to harden the model.

We hoped that unrealistic attacks could help harden models against real-world threats, so we tested the impact of unrealistic attacks alongside realistic ones across three distinct domains: text classification, botnet detection, and malware detection, each presenting unique challenges.

-

Text classification: Simple tricks like character swaps provided only modest improvements in robustness, while attacks that preserved meaning, such as swapping words with synonyms, were far more effective.

-

Botnet detection: In this domain, the model’s vulnerabilities aligned closely with even simple, unrealistic attacks, making the hardening process more forgiving.

-

Malware detection: This proved the toughest case. Unrealistic attacks failed entirely because they never reached the model’s true blind spots, leaving the system exposed.

Across these domains, it became clear that the effectiveness of unrealistic hardening depends on how closely attacks target the model’s critical weaknesses.

We also tried increasing the number of unrealistic examples used in the hardening process for malware and botnets to see if it was simply a matter of quantity, but the results did not change.

These results show that robustness isn’t about generating more examples, but about generating the right ones. Unrealistic attacks only help when they push the model in the same direction and touch the same critical features as real attacks. In our study, this alignment occurred for botnets, where even cheap, simple attacks nudged the model toward real robustness. For malware, however, the alignment didn’t exist. No matter how many unrealistic examples we produced, the models remained exposed.

Looking at these outcomes, it’s easy to see the next step. First, a model trained on unrealistic attacks may seem secure, but real robustness is measured by its response to realistic, unseen threats. Second, even small sets of realistic adversarial examples can be extremely valuable, acting like a compass to guide cheaper, easier-to-generate attacks toward the most critical vulnerabilities. Instead of relying solely on toy attacks for convenience, we should focus on shaping them to reflect the characteristics of real-world threats.

The stakes of ignoring realism in adversarial hardening are high. A model that seems robust in the lab may still fail catastrophically when faced with real-world attacks, leaving organizations vulnerable to malware, spam campaigns, or network intrusions. Overconfidence in lab-tested models can lead to wasted resources, false security, and even regulatory or reputational consequences if attacks succeed. By focusing on realistic adversarial examples, even a small carefully curated set, we can guide cheaper, simpler attacks toward the model’s true weaknesses, ensuring that hardening translates into real-world resilience. In short, as we emphasized realism in testing, we must demand it in hardening.

A note on scope and generalization:

When presenting results by domain (text classification, botnet detection, and malware detection), we used a fixed model architecture, a fixed hardening strategy, and a fixed feature representation for each domain. As a result, the findings within each domain may not generalize to other architectures, hardening methods, or feature sets. Future work could explore more expansive settings, similar to the approach taken by Bostani et al. in On the Effectiveness of Adversarial Training on Malware Classifiers.

Note: This blog series is based on research about the realism of current adversarial attacks from my time at the SerVal group, SnT (University of Luxembourg). It’s an easy-to-digest format for anyone interested in the topic, especially those who may not have time (or willingness) to read our full papers.

The work and results presented here are a team effort, including Asst. Prof. Dr. Maxime Cordy, Dr. Thibault Simonetto, Dr. Salah Ghamizi, (to be Dr.) Mohamed Djilani, (to be Dr.) Mihaela C. Stoian and Asst. Prof. Dr. Eleonora Giunchiglia.

If you want to dig deeper into the results or specific subtopics, check out the papers linked in each blog post.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: